DUNS SCOTUS PRESENTS A MANIFESTLY different doctrine of man, his nature, and morality and natural law relative to St. Thomas's teaching or the teaching of any other Aristotelian-based eudaemonistic ethic. Scotus's emphasis on freedom and the tenuousness of being (which were discussed in the last posting) lead naturally to a "thin" concept of nature, one that while perhaps not completely nominalistic, is certainly less essentialist than an Aristotelian-influenced moral philosophy.

A thin concept of nature means that Scotus must look elsewhere for the basis of moral law, and that "elsewhere" is an ordered freedom, a free act of will that focuses away from one's self and natural desires and is other-regarding and so transcending of one's nature. Indeed, ultimately it is to the Other, to God that Scotus turns. "Scotist morality requires a radical transcendence of the natural," Wolter, xii, and obviously reaches out to the supernatural.

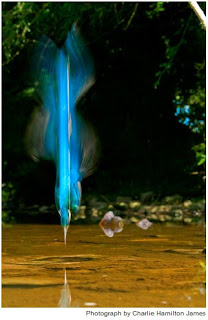

In discussing the role of nature and the need to transcend it, Scotus differentiates between two loves or desires. The first is an affectio commodi, which is a desire that relates to one's self, one's nature, an affection for what is convenient, comfortable, self-satisfying. It looks at activity with a focus on bonum sibi, the good to itself, and not the good of the other. It is a natural appetite, something man would share with all created natures, all "mortal things" whether they be a stones, trees, or a kingfishers or a dragonflies. An act moved by affectio commodi is not so much an act of free will, but rather an act of nature, and so an act not altogether free since it is determined in a real fashion by the impulse of nature.

The other affection, upon which the entirety of morality is built and through which one transcends his nature, is the affectio justitiae. This affectio justitiae (affection for justice) takes a person outside himself and his nature so to speak, and so requires an act of free will, a will freed of its nature and therefore transcending that nature. Contrary to the affectio commodi (which is self-regarding and seeks bonum sibi, and leads to natural happiness), the affectio justitiae is other-regarding. It seeks the bonum in se [good in itself] of things, not the bonum sibi [good to one's self] of the affectio commodi. Ultimately, if properly focused upon the Other, that is, God, the affectio justitiae leads to beatitude. It is through the affectio justitiae that man is transformed from beast to human person. "This transformation lies at the heart of rational personhood." Wolter, xii. It is through the affectio justitiae that man does "more" than "what I do is me." It is through the affectio justitiae that the "just man justices" as he regards things, not from his own perspective, but from perspective of the Other, acting "in God's eye," as it were.

Clearly, with his focus on transcending nature--the affectio commodi--and realizing freedom and moral worth through a nature-transcending affectio justitiae, Scotus deprecates nature as a source of morality.

Wolter, xii.

This Scotist doctrine is oddly existential in feel, and more than one commentator has attributed to Scotus an incipient existentialism. In their deprecation of nature, Scotus and Sartre go hand in hand.* Scotus was an existentialist before existentialism was cool. What separates Scotus from Sartre, however, is the role that the love of God plays.

Wolter,xii. In Sartre, man is condemned to be free, and God plays no role. In Scotus, man is called to be free, and he finds his freedom in the single great principle of all law and morality, the love of God. Deus est diligendus! Ord. IV, d. 46, q. 1, n.1. "God is to be loved!" is, for Scotus, the moral absolute, the irreformable, necessary and exceptionless norm of all moral action. It is the Deus est diligendus! which separates Sartre and Scotus and puts them at antipodes of each other. Not all existentialists are the same.

_____________________________________

*Sartre's deprecation of human nature as a source of moral standard is discussed in Man is Not a Pickle: The Sartrean Argument Against Natural Law.

A thin concept of nature means that Scotus must look elsewhere for the basis of moral law, and that "elsewhere" is an ordered freedom, a free act of will that focuses away from one's self and natural desires and is other-regarding and so transcending of one's nature. Indeed, ultimately it is to the Other, to God that Scotus turns. "Scotist morality requires a radical transcendence of the natural," Wolter, xii, and obviously reaches out to the supernatural.

In discussing the role of nature and the need to transcend it, Scotus differentiates between two loves or desires. The first is an affectio commodi, which is a desire that relates to one's self, one's nature, an affection for what is convenient, comfortable, self-satisfying. It looks at activity with a focus on bonum sibi, the good to itself, and not the good of the other. It is a natural appetite, something man would share with all created natures, all "mortal things" whether they be a stones, trees, or a kingfishers or a dragonflies. An act moved by affectio commodi is not so much an act of free will, but rather an act of nature, and so an act not altogether free since it is determined in a real fashion by the impulse of nature.

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies dráw fláme;G. M. Hopkins, "As Kingfishers Catch Fire."

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I do is me: for that I came.

The other affection, upon which the entirety of morality is built and through which one transcends his nature, is the affectio justitiae. This affectio justitiae (affection for justice) takes a person outside himself and his nature so to speak, and so requires an act of free will, a will freed of its nature and therefore transcending that nature. Contrary to the affectio commodi (which is self-regarding and seeks bonum sibi, and leads to natural happiness), the affectio justitiae is other-regarding. It seeks the bonum in se [good in itself] of things, not the bonum sibi [good to one's self] of the affectio commodi. Ultimately, if properly focused upon the Other, that is, God, the affectio justitiae leads to beatitude. It is through the affectio justitiae that man is transformed from beast to human person. "This transformation lies at the heart of rational personhood." Wolter, xii. It is through the affectio justitiae that man does "more" than "what I do is me." It is through the affectio justitiae that the "just man justices" as he regards things, not from his own perspective, but from perspective of the Other, acting "in God's eye," as it were.

Í say móre: the just man justices;G. M. Hopkins, "As Kingfishers Draw Fire."

Kéeps gráce: thát keeps all his going graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is –

Christ . . . .

Clearly, with his focus on transcending nature--the affectio commodi--and realizing freedom and moral worth through a nature-transcending affectio justitiae, Scotus deprecates nature as a source of morality.

In Scotus' philosophy, "nature" underdetermines the content of morality and the good we achieve through our free will. "'Action in accord with right reason,' therefore,picks out what is reasonable or rational . . . But it is not something suited to the nature of the agent. Being moral cannot be analyzed in terms of an agent's nature, because being free is precisely not being 'in' a nature." In effect, morality arises from the discontinuity between the natural and the voluntary. "Nature" does not suffice to specify the content of morality: it can only give us the good in the eudaemonistic form of the bonum sibi [the good to oneself].

Wolter, xii.

This Scotist doctrine is oddly existential in feel, and more than one commentator has attributed to Scotus an incipient existentialism. In their deprecation of nature, Scotus and Sartre go hand in hand.* Scotus was an existentialist before existentialism was cool. What separates Scotus from Sartre, however, is the role that the love of God plays.

Transcending freedom, of course, has its measure [in Scotus]; it is not arbitrarily open-ended [as it is in, say Sartre], for its object is the bonum in se of things and, most especially, the love of God.

Wolter,xii. In Sartre, man is condemned to be free, and God plays no role. In Scotus, man is called to be free, and he finds his freedom in the single great principle of all law and morality, the love of God. Deus est diligendus! Ord. IV, d. 46, q. 1, n.1. "God is to be loved!" is, for Scotus, the moral absolute, the irreformable, necessary and exceptionless norm of all moral action. It is the Deus est diligendus! which separates Sartre and Scotus and puts them at antipodes of each other. Not all existentialists are the same.

_____________________________________

*Sartre's deprecation of human nature as a source of moral standard is discussed in Man is Not a Pickle: The Sartrean Argument Against Natural Law.

No comments:

Post a Comment